I like to tell you my inspiration for some of these posts because I feel it’s important that you know I don’t spend my entire life thinking about science. Just quite a lot of it. The major thoughts for this one came from an episode of The Big Bang Theory (yes, I’m one of those people who genuinely find it funny) entitled ‘The Anxiety Optimization’. In this particular episode the main character, Sheldon, is trying to become more productive and states that “in order to maximize performance, one must create a state of productive anxiety”. He attributes this maxim to a study by Yerkes and Dodson, a paper from 1908 which accidentally spearheaded a whole series of articles on the potential for external stimuli to affect productivity.

So what we’re going to do today is think about the scientific history of stressors and how they affect performance (because it’s interesting and you know by now I like a history lesson), and more importantly how this fits into the context of academic life and mental health and what we can do about it.

We’ll start in 1908 with Yerkes and Dodson for no reason other than that’s where everyone seems to start. The ‘Yerkes-Dodson Law’ is an empirical relationship between external pressure and performance. In their 1908 paper they studied the capacity for mice to learn effectively when being subjected to external stimuli, in this case either food withdrawal or electric shocks. What they discovered was that learning and stimuli form a U-shaped curve.

At the low levels of shock intensity, the mice learned slowly. Essentially there was no ‘motivation’, for want of a better word. As the intensity of the electric shocks increased, they learned faster. However, at a certain point the shocks became distracting and their learning speed dropped off again and they became more error prone.

In 1908 Yerkes and Dodson studied the capacity for mice to learn effectively when being subjected to external stimuli, in this case either food withdrawal or electric shocks.

Slight barbarity aside I can hear you say, ‘but these are mice, how is this relevant to humans?’…I’m getting there.

The results from this paper were sort of ignored for about 50 years until someone called Broadhurst brought them together with a bunch of other studies in a review in 1957. One of these studies was by Vaughn and Diserens in 1930, which essentially replicated Yerkes and Dodson but in people. They challenged 18 participants to undertake a stylus maze, the sort you get in puzzle magazines, whilst being subjected to different intensities of electric shock. Which you can imagine made the whole thing much less relaxing.

They found, as Yerkes and Dodson had, that “an increase in the intensity of punishment created a readiness and an eagerness to react that was not typical for the preceding intensity”. Basically, at low levels of shock the participants tended to exit cul-de-sacs quicker and get to the end of the maze faster than when there was no threat at all. At higher levels, the participants tended to make more errors, turning down blind alleys and taking wrong entrances.

But what does this have to do with academic life?

As mentioned in a previous post, there is an inherent pressure in academia to deliver. To deliver consistently and to deliver well. No papers, no grant, no job, blah blah blah. This can be viewed as a real-life example of the Yerkes-Dodson Law in action and if you go into any academic institution, you’ll find it to be the case. Tenured researchers can be very laid back, they have no real need to do research because they have a permanent job so realistically, why try? There is no external pressure stimulus on them so they’re sitting at the left-hand end of the Yerkes-Dodson graph. On the other hand, early career researchers are trying so hard to please everyone – the grant review boards, the teaching panels, the students, the publishers, the lab manager – that they end up basically doing nothing because they’re so busy trying to do everything else. Here the external pressure is too great and they’re sat at the far right of the graph.

So if we are sat at the far right of the graph, where the pressure is making us unproductive, what happens?

In 2020, The Wellcome Trust published a study called “What Researchers Think About the Culture They Work In” which interviewed 4,000 participants, most of them in the UK, about research culture. Of those, around one third reported having sought help for depression or anxiety. One third. This is going to sound dumb but…that’s a lot. These guys are all sat at the far right of the graph and as a result they’ve developed serious mental health issues. The study concluded by saying this was essentially going to result in a brain-drain, they said that “A culture that neglects researchers’ health, wellbeing and work-life balance may have consequences that affect the sustainability of the sector; it may reduce the quality of the research produced and lead to the loss of research talent”.

But for those of us not leaving the sector, what can we do about it? There are a bunch of ways we can think about this, so let’s start selfishly with our own mental health and wellbeing.

My first piece of advice is potentially bad. On this occasion, I believe that comparing yourself to others is a good thing to do. Let me justify that statement. If you are working for someone who expects you to start at 8am and work until 8pm, who doesn’t check in on how you’re doing, who doesn’t discuss your science with you, then that’s not a good thing. But if you’ve never experienced anything else then maybe you think this is how the ‘cutthroat world of academia’ is supposed to work. So, having a peer support network is really important. Is everyone else also pulling those hours? What kind of support do they get?

So, if you’re working hours are normal and your boss is supportive and you’re still anxious what can you do? There’s a couple of obvious and basic things that I think help.

Day-to-day try and make lists and tick things off. These can be as basic as ‘email Fred’. The act of ticking something off makes you feel like you’ve achieved something. And try not to worry about the unticked items, you’ll get round to them eventually.

Have a little perspective. Sometimes science feels like you’re shouting into the void and nobody cares, and as a career choice this is basically a guaranteed path to anxiety and depression. So, take some time to realise that almost everyone is in the same boat. You are fighting the system, not some personality flaw of your own. This is not your fault.

And finally talk about it. If you are genuinely struggling with your feelings seek help. Whether that be from your peers, from your mentors, or from professionals.

One thing I find helpful if I’m in the right mindset is flinging myself into fixing someone else’s life. As an early career researcher, you might be in charge of younger colleagues or students. A good mental health check-in on them every now and then is a nice thing. You don’t need to be patronizing about it. Perhaps just open a meeting with “How are you doing?”, which is what one of my favourite PhD supervisors did. It gave me the opportunity to say ‘fine’ if everything was fine, or it gave me the opportunity to cry and say I wanted to leave science because it never worked anyway and what was the point. And what she did during that time was listen, which was all I sometimes needed. And, in turn, it gave her the opportunity to put things in perspective for me and say that sometimes things didn’t work, chill out, calm down, etc.

But on top of the basic check in, I think it’s also broadly important to be aware of the different needs of your team and those around you. Knowing that your student is working every weekend, is extremely stressed and is basically running on fumes should prompt you to find out why. Are they worried about failure? Are they panicking about a deadline? Or is there something going on in their personal life that is making them throw themselves into work? Is there anything you can do to help? Even small things like telling them they’re doing well, or occasionally buying them lunch so they don’t need to down tools will alleviate some of the anxiety they might be feeling.

For those genuinely struggling there are lots of resources out there which are fantastic. From the basic mindfulness apps which might help them calm down and focus, to websites like Mind, which will point them towards professional help if they need it. Whilst institutions are now going out of their way to support the mental wellbeing of their staff with courses on meditation and so forth, the fundamentally tenuous nature of the job means these things are often just window dressing, so the actual day-to-day job of keeping an eye on things falls to team leaders and those around them. It is our job to encourage both work-life balance and an open conversation about mental health in the workplace.

So my concluding advice to you is…don’t get all the way to the wrong end of the Yerkes-Dodson curve before asking for help. Chances are someone else has been there before you and can help you put it all into perspective.

Dr Yvonne Couch

Author

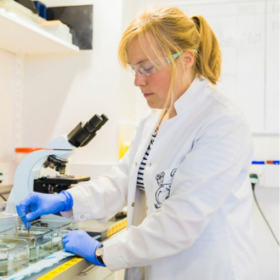

Dr Yvonne Couch is an Alzheimer’s Research UK Fellow at the University of Oxford. Yvonne studies the role of extracellular vesicles and their role in changing the function of the vasculature after stroke, aiming to discover why the prevalence of dementia after stroke is three times higher than the average. It is her passion for problem solving and love of science that drives her, in advancing our knowledge of disease. Yvonne has joined the team of staff bloggers at Dementia Researcher, and will be writing about her work and life as she takes a new road into independent research.

Print This Post

Print This Post

Going on this calls for self-care, understanding, and seeking support. Acknowledging these feelings, one can take steps towards regaining balance and finding a more stable emotional ground. Standing on the edge of anxiety feels like a constant balancing act, wobbling between worry and calm. Thanks for sharing information about this anxiety.