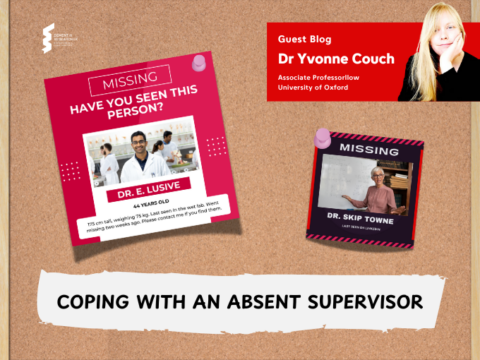

Welcome to our mini-series on post-doccing in the 21st century, where we discuss the highs, the lows, the problems and the potential solutions. In this series Dr Yvonne Couch, ARUK Research Fellow from the University of Oxford is joined by Dr Kritika Samsi, Senior Research fellow at King’s College London, Dr Sarah Kate Smith, Research Fellow at Sheffield Hallam and one of our new regular bloggers at Dementia Researcher Dr Kamar Ameen-Ali at the University of Glasgow.

In this first episode they share their years of experience in academia and outside of it to generate some sage advice for the next generation. Tune in to find out more + comback on Wednesday for the next installment.

All this week Dementia Researcher is publishing content aimed providing help, advice and support for anyone who feels a little ‘stuck’ at the postdoc career stage. Ideal for anyone looking to break out into indepednant research, avoid ever getting in the situation, hoping to work out how to get a promotion or accept this but challenge the issue of short-term contracts.

Voice Over:

Welcome to the NIHR Dementia Researcher Podcast brought to you by dementiaresearcher.nihr.ac.uk, in association with Alzheimer’s Research UK and Alzheimer’s. Society supporting early career Dementia Researchers across the world.

Dr Yvonne Couch:

Hi, everyone. Welcome to the Dementia Researcher podcast. My name is Professor Yvonne Couch because apparently I’m allowed to use that title now. I’m an Alzheimer’s Research UK fellow and associate professor of neuroimmunology at the University of Oxford. And I’m excited to return to hosting for this mini-series about postdoc life. Over the next three mini-episodes, we’ll be discussing the issues with being a perpetual postdoc. Things we wish we’d known when we were early career researchers, things we do to cope with the situation, and things we think we need to be talked about more so that change can happen. Now it should be noted that everyone on the podcast today is a UK researcher. So, whilst some of the problems we’re discussing are global, some are specific to the research environment in the UK.

Dr Yvonne Couch:

Today I’m joined by Dr. Kritika Samsi, senior research fellow at Kings College, London; Dr. Sarah Kate Smith, research fellow at Sheffield Hallam. One of our new regular bloggers at Dementia Researcher, Dr. Kamar Ameen-Ali at the University of Glasgow. Hello everyone. And thank you for joining. So today’s podcast is called 2020 hindsight tips from perpetual postdocs. And what we’re going to do is share some of our stories and some of the things we wish we’d known earlier in our careers, but let’s start with some introductions. Sarah, I know your story is a little bit more unusual than most. You want to tell us a little bit about your background?

Dr Sarah Kate Smith:

Okay. So hi, everyone, my name is Sarah and as Yvonne said, I’m a postdoc at Sheffield Hallam university. I came to academia late, having been a manager at the John Lewis partnership for many years. I completely changed my career path following many years as volunteering as a Samaritan, and was shocked and saddened really to realize how many calls were from older adults and people living with dementia. These people went suicidal, but the Samaritans were their lifeline and their contact, and they were feeling isolated and just wanted a regular conversation with the outside world.

Dr Sarah Kate Smith:

So when my youngest son was six months sold, I enrolled with the open university and did an undergrad in psychology, which I completed part-time whilst bringing my children up. I achieved a First-Class Honors and then secured an ESRC funded fellowship. So sorry, Economic and Social Research Council fellowship, to undertake my PhD in the school of health and related research, at the university of Sheffield.

Dr Sarah Kate Smith:

My PhD focused on people living with dementia and how we may enable people to engage and enjoy digital technology, in line with the rest of the population. So since gaining my PhD in 2015, I’ve held five post oppositions in four different universities in three different cities in the UK, all engaging older adults and people living with dementia and the promotion of digital technology and health and social care context. That’s me.

Dr Yvonne Couch:

Excellent. Thank you. I love the fact that you found your passion later in life. If it’s not too rude of me to say later in life, but I think to go back and find like that niche that you love, I think is wonderful. Kritika, you are a little bit like Sarah, you work more with the sort of frontline with patients with dementia. Do you want to tell us a little bit about that and how you got to where you are?

Dr Kritika Samsi:

I think that is probably the only overlap I have with Sarah. Hello everyone. So, my career trajectory has been almost the opposite of Sarah’s in that I did my degree in India in psychology, I came to the UK to do a master’s in Gerontology, and then I started working as a researcher at the Institute of psychiatry, psychology and neurosciences, and a PhD opportunity presented itself on the job I was working on. I did the PhD part-time and I’ve literally stumbled into academia, but gerontology, psychology, dementia, they’ve always been something I’ve really been and enamored by, it’s something I really wanted to work in.

Dr Kritika Samsi:

So in every way it has all worked out for me, but I’ve just worked in the same field for a number of years. I’ve worked in Kings college for almost all of my career. I did my masters at Kings, my PhD at Kings, and now I’ve been working at Kings for over 15 years. So like I said, it’s almost exactly the opposite of Kate. I’ve had a number of postdoc projects and a number of postdoc projects and studies, but not different jobs or moved universities. So I’ve not had the same experiences as Sarah in that way, but I am in the same position now as Sarah is.

Dr Yvonne Couch:

Excellent. And it’s useful in terms of perspective, to have those two different sides of the coin, that you worked consistently in one place. And that Sarah’s had to shift around a lot. I think in terms of helping out the early career researchers that we are aiming this at, I think to have those two different perspectives is really important. So Kamar, I know that you are much more like what I call a fundamental researcher, because I do not like the term basic researcher, and I know you left academia to work in research report, and then you came back. Can you tell us a little bit about why you made that decision and what your research focuses on now?

Dr Kamar Ameen-Ali:

Yeah. So to give you a bit of background, I started with my undergrad in psychology college at Durham university. And following that I stayed to do a master’s in cognitive neuroscience. I found that what I was really, really interested in was kind of the neuroscience side of psychology, but I never planned to do a PhD. I never planned to work in academia. What I really wanted to do was be a clinical psychologist in the NHS, but then the chance of doing a PhD at Durham was offered to me. It was work that naturally followed on from the project that I’d done during my master’s degree. And so I took that opportunity. So my PhD involved, basically trying to understand the mechanisms of understanding memory and how we process memory using a lot of animal models, but also doing some human experiments as well.

Dr Kamar Ameen-Ali:

From that, I then moved to Sheffield University for my first postdoc, where it was almost like a natural progression. So I did more work with an Alzheimer’s mouse model. So it involved again doing those kind of cognitive behavioral studies with the rodents. But I also started doing more neuropathology as well, which I really, really enjoyed. When I came to the end of that contract, I was applying for other postdoc positions, but the opportunity to work as a [inaudible 00:07:12] manager for the NC3Rs, which are a research funder in the UK, came up. And I didn’t make a conscious decision to leave academia because I wasn’t enjoying it or I was having a bad experience, but I tried to be open-minded and I was applying for postdoc positions as well, but that opportunity came and I applied for that and I got it. So I worked for them for two years and I really, really enjoyed it.

Dr Kamar Ameen-Ali:

The reason why I went back to academia after working with the NC3Rs for two years was even though I enjoyed and loved everything that I was doing with them, I was doing a lot of traveling, so that to me wasn’t sustainable long term. So I decided to go back to research with a postdoc position at Newcastle University. That was a very short contract, but then I moved to Glasgow University, which is where I am now, working as a research associate. And the project that I’m on now is really, really interesting. So I’m studying traumatic brain injury and how that is a risk factor for neurodegenerative diseases that lead to dementia. So broadly in my research career, it has involved understanding memory, it’s involved neuropathology, but it’s all under that umbrella term of dementia and trying to understand what happens in the brain of people that have dementia.

Dr Yvonne Couch:

Excellent. Thanks Kam. And I think you’ve brought up a lot of really interesting points in terms of having to move around a lot, having to commute a lot and making your life decisions based on that. And I think that’s definitely going to come up in the discussion that we’re going to have shortly. So, let’s kick off today’s discussion with a pretty specific question. What would we have wanted to know about academic life when we were approaching the end of our PhDs or even before we were considering starting a PhD? who wants to kick it off?

Dr Kamar Ameen-Ali:

I don’t mind going first. So I think even though my PhD was such a good experience, like I think there’s nothing about it I would’ve changed the environment, the project or my supervisor, they were all great. But one thing that I advise my students now is if they’re thinking about applying for PhDs is to really consider that, I think a lot of them think about the project being the most important thing and really finding the perfect project for them. But I think that there’s more value on having a good supervisor and being in the right environment. And I would place more value on those things than the actual project. So even though I didn’t need that advice, I kind of fell to a good environment and a good project and a good supervisor. It’s the advice that I would give my students now.

Dr Kamar Ameen-Ali:

And the reason why that is, is because course PhD, you might move out of academia or you might move into an adjacent research area like I have, if you go onto a postdoc position. So I think it’s really, really important to do a PhD in a supportive environment. Even if the project isn’t necessarily the perfect project, I don’t know the technique that you want to use, the methods that you want to use, but ideally you could have both, but it’s unrealistic, but I think definitely it’s preferable to be in a better environment with a great supervisor than on a perfect project.

Dr Kritika Samsi:

I completely agree. I’m taking it the next step and think that’s even important at the postdoc level. I feel like I’ve got to where I have and the reason I stayed at my university for so long has been principally because I felt I’ve been lucky. I feel like I’ve got a really supportive manager as well as a team, as well as the junior researchers coming through are also amazing and really supportive. And it’s been a really lovely flourishing environment, but I feel like the systems in place, we shouldn’t be depending on luck. I feel the systems in place are not enabling where the, luck shouldn’t be the only factor, I feel like the current systems are depending on luck, taking early career researchers and postdocs through to these positions. And then if you don’t have a good supervisor or you don’t have a good research team or a good environment, the system really fails you.

Dr Kritika Samsi:

And I think that’s why I was keen to do this podcast because I feel like I’ve been lucky. I’m not here to complain about how hard it’s been. I’m more kind of aware that it’s not like that for everyone. And something needs to change because everyone’s luck is going to run out at some point, including mine, but also it shouldn’t be luck that kind of brings us to this point. So I definitely think the environment you’re with and the manager and the research team you’re working with plays a really crucial role in, I’m sure, PhD level, but also at postdoc level and beyond.

Dr Yvonne Couch:

Yeah, I completely agree. And one of the things I think is important to maybe stress to early career people is that you maybe do have to be a little proactive. You do have to like with my very junior, if I have people coming into the lab with undergrads and things, if I have them coming in saying they want to do a PhD, I say, one of the things you need to go, is you need to go and visit the lab. You need to talk to the people in the lab, ask them really honest questions. Like, “Do you enjoy working here? Is your boss nice?”

Dr Yvonne Couch:

I have in previous labs specifically said to new members who want to join the lab, I say, “If you want to join this lab, you need to be aware that you will never see your boss, he’s extremely busy.” I said, “If you want to be supervised by him, it’s going to be very unlikely. You are more likely to be supervised by me. So, that means you have to get on with me rather than him. But if you are here for him, then you’re not going to see him. He’s got a million different projects. He’s only here for 20 minutes a week.” So I think that kind of degree of honesty from the people within the lab, but also that kind of degree of motivation from other people I think is really important. Sarah, did you want to jump in?

Dr Sarah Kate Smith:

Yeah, I think I agree with what everyone is saying here. I was really quite naive when I joined academia and wrongly assumed that, so there was a sure fire path after doing a PhD to a permanent position, I didn’t realize actually what was happening, although I’ve been fortunate to align my postdoc. So I have never been out of work. It does come with periods of stress and anxiety when you are looking for something and give yourself three months to line the next job up or what have you. But it’s definitely a career path for those that, not a career path for those that require stability, I think that would be a huge issue. I agree with everyone when there’s talking about the supervisor and my PhD was already funded when I applied for it. So it was my supervisor’s idea and she chose the candidate that she wanted to, who she thought would be suitable.

Dr Sarah Kate Smith:

And she was what built my career, that woman. And I’m not saying it was the easiest relationship, but we are colleagues now and we’ll be friends forever because it was a really, really positive relationship and we weren’t in competition, she wanted to develop me and pass on everything that she had learned. So, and it was where it as well it was such the such good grounding for my training. Definitely.

Dr Yvonne Couch:

Yeah. And I think that definitely helps. And I think I did kind of similar things. I almost blundered into academia, very naively. And like you say, I sort of assume that you’ve got all these qualifications, you have to get a job at the end. Right. And because you are sort of surrounded by academics, you just kind of assume that that is what your job is going to be. But Kam, I know you moved out because you’ve said wanted to have more of an open-mind about sort of other opportunities that are available. Do we think that part of the problem here is that there aren’t really other opportunities outside? Do we think that basically, if you don’t stay in academia, you are almost considered a failure. And how do we highlight that there are other things that you can do after you finish a PhD?

Dr Kamar Ameen-Ali:

Yeah, I do feel like there is a narrative around those who choose to leave academia because it’s not always acknowledged that some people might choose because they discover what they really, really want to do. The great thing about doing a PhD is you, and actually doing research in general, is you do lots of different activities. So day to day, I can be doing lab work, data analysis, writing, these all require very, very specific skills. And the good thing about doing a PhD is it gives somebody the opportunity to develop these skills and decide, whether they really, really enjoy or are really talented at doing one of those things. So for example, if they’re really, really talented at writing, they might choose to leave academia after their PhD because they’ve discovered what they really, really enjoy doing. And that should be celebrated. It shouldn’t be seen as, “Oh, another person is leaving. That’s a failure.”

Dr Kamar Ameen-Ali:

I feel like as well, we need to support more people at the PhD level in terms of letting them know the different career options that are available after a PhD. Because I feel like a lot of the time it is just this perception of a linear progression following the PhD. And you’re kind of left to find out about these other career options yourself. And I feel like universities are getting better at promoting them and having events and workshops and things like that. But it’s certainly not perceived as a positive, if you leave academia. I feel like that’s the narrative at the moment.

Dr Yvonne Couch:

Yeah, definitely. And I think there’s still some, definitely within universities, I feel like the careers advice teams are often still a little bit sort of set in their ways. I know that as, I admittedly, I was an undergrad a really long time ago, but when I was an undergrad, it was almost like, well, you’re doing a science degree, you’re going to have a job in science. That’s the way it works. And I just feel like that’s not the case. And there are so many other things, whilst you do gain a lot of really specific skills during a PhD, like, I know exactly how to get to really tiny blood vessels in a mouse neck, and that’s not necessarily a transferable skill, but I do then technically have very great manual dexterity.

Dr Yvonne Couch:

I have writing skills. I have, you know, that kind of transferable skill that you can use in other career paths. And I feel like there is this, because you’re surrounded by academics it feels like that is the only option. And universities, I don’t think are, like you say, celebrating enough that actually you’ve got this skill. Maybe you’d like to be elsewhere. Kam, go ahead.

Dr Kamar Ameen-Ali:

Yeah, I feel as well, sometimes it’s the terminology that’s used, so when they are discussed, they’re talked about as alternative careers, but that suggests that having that career in academia after your PhD is the norm. As soon as you use the word alternative, it suggests that that is the norm. And I feel like if we just change the narrative around it to these are all the careers that you can have after your PhD. None of them should be considered the norm and none should be considered alternative.

Dr Sarah Kate Smith:

I think it, to be honest, actually it never occurred to me to leave academia. And I don’t know if it was because it wasn’t a choice. I didn’t realize there was a choice. I thought that rightly or wrongly, that I did my training here and then I carried on. And that, again, it’s a naive way, but I think it was the ethos of the institution I was in. And they training for their postdocs and you weren’t expected to leave, really.

Dr Sarah Kate Smith:

I think some of my peers did go into industry roles. But I was always very sure that I wanted to apply what I’d learned in my PhD, in a full-time job. And it was always about people living with dementia and I felt the best way I could impact positively on their lives was to continue in academia. And that was how I was going to build the evidence and make a difference. It’s just a different perspective, isn’t it?

Dr Yvonne Couch:

It is. It’s completely different perspective. And I think, like you say, if you are sort of within that environment, it’s almost where you get stuck, but there’s also this, like Kam says, there’s this narrative around leaving. I know that I had a student who wanted to go into, she wanted to go into science communication, and she’s enthusiastic and she’s really outgoing, and as a Scicomms person, she’d be really good. And I even remember, like even with my attitude towards this, I remember having a conversation saying she’s leaving science, it’s a shame. And I just felt that’s not the right thing to say. It’s not a shame. It’s not a shame for her, especially not if it’s what she’s passionate about. And it’s what she’s good at. I don’t think it should be considered a shame that she’s changing her career path because she wants to do something she enjoys. I don’t think that’s necessarily a bad thing.

Dr Yvonne Couch:

So I’m hoping that as all of the old white guys sort of start to retire, that maybe we can maybe change the culture and change the ideas. But also we just need to know, I think more about these alternative careers, not alternative, I’ve just said it I’ve made the mistake. I’ve already done it. I am the perpetrator of all of this. Kam, you went to the NC3Rs, how did you find out about the job? Did you go job hunting or did it just come up or how did it happen?

Dr Kamar Ameen-Ali:

Well, so the NC3Rs actually funded my PhD. So I actually knew about them as a research funder in the UK. And the great thing about the NC3Rs is they’re very personable. So they organize a lot of events. So those that they fund, you get to interact with the staff there. And so roundabout, when I was coming to the end of my first postdoc, these new regional program manager roles were being created, and I just thought I would take the opportunity to apply. And I think that I was quite early in my career to be applying for a job like that. But because of my experience working around the 3Rs and applying the 3Rs, I mean, for those who don’t know, the 3Rs are the refinement, replacement and reduction of animals in research. So the whole point of the NC3Rs is they fund research with the aim of funding ethical use of animals and reducing the number of animals in biomedical research.

Dr Kamar Ameen-Ali:

So I kind of knew what they were about. And I had that knowledge of kind of things that they were doing, activities they were involved in, which played to my advantage. So a lot of luck was involved in me getting that job, but I was so excited to be working for them, that’s why it was an opportunity that I really felt I should take. But at the time, because I was also applying for other postdoc jobs, similar to what Sarah was talking about, if it wasn’t because I already knew about them, I wasn’t exploring other options. My other options would’ve been to stay in the research area that I was working in and to progress that way. It was just because that seemed like an opportunity that I had some familiarity with already.

Dr Kritika Samsi:

This is not in direct relation to Kam’s point, but I know we’re talking about what we would say to an early career researcher, but I feel like a lot of us might be a few studies in, and we’ve done postdocs for a while. And I feel like I’m now at point where I’m not considering leaving academia for good or bad reasons. I’m very happy here. It’s not a problem, but even if I was, because I’ve done a good few postdoc studies and I’m struggling to make the leap into more of the senior roles, I feel like leaving academia would take me back to being a starter in a new career. So just out of a PhD, having those options is almost easier than the point I am at now, which is a more senior academic. And then going into science communications or a policy maker at a charity, would take me back to being a new learner. And that is something I may not be willing to take on. So I feel like at this stage of my life, I have even less options.

Dr Yvonne Couch:

Yeah. I think one of the things that came up when we had a bit of a pre-chat before this episode was that we should, or people should maybe consider that a PhD is just training. It’s just a degree. It doesn’t necessarily instantly mean you have to do something related to it afterwards. You can do a PhD in something and then move fields. You can do a PhD in something and then move into something that is non-science related. A lot of people go into a consultancy and things like that. And there’s even scope, potentially to do, what I found a lot of people who now don’t work in academia have done is they did a PhD and then they did one postdoc because I find that the experience of a PhD where you’re almost depending on your supervisor, you’re almost very closeted, you’re sort of looked after for the entire time and it doesn’t matter if you make mistakes, whereas a postdoc you are sort of almost considered, these experiments are very much your responsibility.

Dr Yvonne Couch:

And these are the outcomes that we definitely need. And a lot of people don’t necessarily enjoy that experience. And so we’ll choose to leave after one postdoc. But yeah, I agree with you, Kritika. I go on and off the fence about academia, especially recently, especially with the pandemic and funding being so difficult. I sort of jump on and off, but the idea of, like you say, going into something completely new and almost being like a fresh recruit despite the fact that I now have sort of 10 years of science experience, what on earth would I do? I think I’d be terrified. Sarah, jump in.

Dr Sarah Kate Smith:

I’m sorry. I just wanted to make a point that this isn’t going to be everyone’s experience, but I wonder how much it’s got to do with age or generations or when you’re starting a PhD. I do feel that my experience has been different because I was a mature student. Me and my PhD supervisor agreed right at the beginning that it was a job. And we worked together in the office nine to five, Monday to Friday. So there was other PhDs students who chose to work 12 noon till 10:00 PM at night or whatever. I couldn’t do that because I had a young family and responsibilities at home. So it worked very well for me in that sense.

Dr Sarah Kate Smith:

But I was also told that, or it was alluded to, that I had to maximize my chances of career progression. I had to be flexible and go where the opportunities were, once the PhD was over, that was always drummed into me. Which was a real challenge because my husband earned much more than me and had a permanent job. So he wasn’t going to move. We weren’t going to move because of my job. Because his job trumped mine every time. And my kids were at school in locally and I wasn’t going to move. So every time contracts came up, my options were always limited to what was commutable.

Dr Yvonne Couch:

Okay. So if we assume we’ve got an early career researcher listening, who does want to stay in academia, Sarah, do you think your tip for them would be to always have a plan B?

Dr Sarah Kate Smith:

I think always have a plan B and C and D. I think I put all my eggs into one basket, which was fine and again it was naivety, but it does come with a few stressful moments when the contracts are coming to an end. But I do believe that if you have the freedom and the possibilities of relocating and traveling, and internationally doing this something abroad, I would’ve loved to have done that. So I think the opportunities, if you are not tied to a city, then the opportunities are amazing. So, but I think, yes, definitely a plan B will be a good idea.

Dr Yvonne Couch:

Kritika you jumped countries. What made you come to the UK and would you ever consider going back?

Dr Kritika Samsi:

Well, I moved to the UK to do my masters. So this is almost 20 years ago now. Yeah, 20 years ago now. And I came here to do my masters and I generally just, I’m trying to think of the reason. I don’t think there was ever a plan to go back and now I’m married have family here. So I don’t think I would move back to India necessarily. But I’ve not had the position of Sarah, which is move around the country because obviously I’ve been at the same Institute. And I suppose even if I did need to look around, London has a lot more opportunities, maybe. So in lots of ways, I’ve been spoiled with being where I have been. So I’ve not had the same thing. I think my big advice would be, again, this has worked for me and I realize it’s not for everyone, is I’ve had to be flexible with the projects I’ve taken on.

Dr Kritika Samsi:

So I think it seems like I’ve not worked in dementia all of the past 20 years, even if I would’ve liked to. I’ve tried to find the dementia angle, I do a lot of social care research and I’ve made my peace when it’s not been dementia angle, knowing that the next study could be. So I think my thing would be the flexibility with not moving, but the flexibility with sort of making your peace, if you feel like you like the environment, you like where you’re working, and you see there’s an end in sight to what you’re giving up as it were.

Dr Yvonne Couch:

Yeah. Yeah, definitely. And I think I’ve had the opportunity of a bunch of different projects recently and some of them are really exciting and some of them much less so. And I think if I want to stick around here with life generally being as competitive as it is, I’ve got to almost give up the idea that I have to be doing just this tiny one project because chances of getting that funded and chances of that sort of persisting are lower. So I’ve got to not spread myself too thin, but you know, find other people to work with and be flexible about how I work. Kam, you’ve moved around a lot within the UK. Did you plan on doing that? Do you think that’s something you would advise early career people to do, or in hindsight, would you have preferred to do something more like what Kritika has done and sort of stayed within an institution?

Dr Kamar Ameen-Ali:

I think coming out of my PhD, I wanted to stay where I was, but that wasn’t an option. I didn’t have any funding to stay where I was. And actually I applied for a fellowship coming out of my PhD to stay where I was, but the feedback was that at the time, and I think there was still a lot of senior academics that give this advice, that to do a fellowship, you have to move to another lab from where you’ve done your PhD. And that was actually the feedback that I got on my fellowship application. And that obviously wasn’t successful. So I went and did a postdoc in Sheffield. And at the time I was just taking what was available to me, what I was successful in getting. It actually was a really, really good move for me because if I hadn’t moved to Sheffield, then I wouldn’t have got the job with the NC3Rs because that was based in Sheffield and in Manchester, and Liverpool supporting those universities.

Dr Kamar Ameen-Ali:

So everything kind of led on from each move that I had. And I think looking back, I’ve enjoyed living everywhere that I have lived and I’ve enjoyed working on all the projects that I have. My advice would be just to be open-minded and follow what you are interested in, because that’s what I did. When I moved to Sheffield, I was exciting to be working and doing a lot of those cognitive behavioral tests that I’d spent my PhD developing, but it gave me the opportunity to work with an Alzheimer’s mouse model. And it gave me an opportunity to learn a new skill in neuropathology, which is now all that I do working on human tissue, in doing neuropathology. So I was quite nervous about learning that new skill, but now it’s all that I do. Like I followed what I was interested in and that’s now everything in my research.

Dr Kamar Ameen-Ali:

So my advice would be to follow what you’re interested in. And if you have got the flexibility to move like I did, then it is a great opportunity. It can be quite scary, but it can also be an excellent opportunity. I feel like as well, we need to, and I think it is something that is predominantly with senior academics, but we need to change this narrative that it is necessary if for whatever reason somebody wants to stay where they are, if it’s because of family reasons or because actually that is just the best environment for them to do that project, then we shouldn’t be telling people that they should move for the sake of it. Like that to me is just ridiculous.

Dr Yvonne Couch:

Absolutely. And I think like you say, this is a narrative that has persisted, but there are so many opportunities now to have fellowships where you put in a bit of time in another lab, you go away, the idea is you go away for three months or two months or six months, you learn a new skill and you bring that skill back to the lab that you’re in. And I think those opportunities for growth are really important. I did my first postdoc in Denmark and I was only there for a year, but it gave me a different perspective on how research is done in different places. But it also allowed me to see that actually I was really enjoying being in Oxford naturally. That was a research environment that I particularly enjoyed. And I knew, and I think it could possibly be a bit of status quo bias. “I like it here. And I know how to find things and how to find people who know things.”

Dr Yvonne Couch:

So I didn’t necessarily jump around much as I could have done, but I do think that there is a lot of change happening in terms of that need to move. So my advice would be sort of an amalgamation of all of your advice and that would be, that you need to do what makes you happy. And if what makes you happy is jumping countries and experiencing something completely different, then you do that. If what makes you happy is going into a career in writing, then do that. And you shouldn’t let the status quo or the inherent bias of senior academics let you in any way, move away from what makes you happy and what you enjoy life.

Dr Yvonne Couch:

It’s time to wrap up today’s podcast, which I hope you found useful. If you are starting out on a career in research. Tune in for the next one where we’ll discuss what to do if you are already at the stage where you are trying to establish yourself, which is what a lot of the researchers on this podcast are. Remember if you’re an early career researcher and you’re looking for resources on CVS, cover letters, cold emailing, et cetera, check out the Dementia Researcher website. I’d just like to thank our panelists. Dr. Kam Ameen-Ali, Dr. Sarah Kate Smith and Dr. Kritika Samsi. We have profiles on all of today’s panelists on the website, including details of their Twitter accounts. So feel free to jump on and follow their research. Thank you all for listening and remember to like, and subscribe to the Dementia Researcher at Apple podcast, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts, stay safe and keep researching.

Voice Over:

Brought to you by dementiaresearcher.nihr.ac.uk, in association with Alzheimer’s research UK and Alzheimer’s society. Supporting early career Dementia Researchers across the world.

END

Like what you hear? Please review, like, and share our podcast – and don’t forget to subscribe to ensure you never miss an episode.

If you would like to share your own experiences or discuss your research in a blog or on a podcast, drop us a line to adam.smith@nihr.ac.uk or find us on twitter @dem_researcher

You can find our podcast on iTunes, SoundCloud and Spotify (and most podcast apps) – our narrated blogs are now also available as a podcast.

This podcast is brought to you in association with Alzheimer’s Research UK and Alzheimer’s Society, who we thank for their ongoing support.

Print This Post

Print This Post