Digital interactions could be useful for tracking health states, especially for brain disorders. The problem is that this kind of data may be harder to protect, and less controlled by ourselves. People with dementia, and other cognitive and behavioural problems, are vulnerable to data insecurity. In this blog, I describe what is digital phenotyping, the good and bad aspects of using it, and some future perspectives behind ethical and methodological difficulties. Healthcare professionals and non-clinical researchers need to talk more about that.

Big data, artificial intelligence, blockchains, machine learning. All these definitions related to the “digital world” gained momentum – fortunately, or not – in the last few years. This occurred especially after the rapid new needs of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Direct social contact and communication was more difficult from 2020 to 2022 and we needed more from the online digital tools to solve the problems for our dementia patients. Now, we rely more on video calls, telemedicine, and online shopping than ever. They are really here to stay, and I can’t see things turning back. And you, what do you think?

The hurdle they bring to us is also that our privacy, an important human right, is always being put in proof in online services. In the UK, for example, news points out that ease in digital privacy laws are actively being discussed again, questioning individuals’ controls over their data.

Digital technologies are part of our everyday life and social interactions

There is much interest in studying these interactions, trying to build a so-called digital phenotype. But, do the research regulation and informed consent is enough for approved research and for business use cases? What is really digital phenotyping? How strict should these regulations be in any case? Are people suffering from cognitive problems and dementia addressed and protected? We have some questions, but not many answers.

In the next sections, I will describe what is digital phenotyping, the good and bad aspects of using this kind of approach for dementia and mental health problems, and some future perspectives considering the ethical and methodological characteristics behind that.

What is digital phenotyping

We know, or can imagine, that we have some “digital fingerprints” everywhere: that smartwatch your mom gave you, your nice mobile to connect to the 4G or 5G internet, the online chatting you share with your grandpa, and the complaint form you fill to return a broken delivered good.

As a broad definition, the digital phenotype refers to all the moment-by-moment quantification characteristics of the individual-level human phenotype using data from personal digital devices. The promise of digital phenotyping is that those objective measures happen in the context of a patient’s lived experience, reflecting how we function in the world, not in our clinics.

This type of data collection may converge with neuroprosthetics and other types of biological data, but is believed to have better ecological validity, i.e. the information is taken out while performing daily tasks beyond a lab-controlled environment.

The (real) goods

This type of data is especially useful in diseases that alter not an easily identifiable cause, but rather the human function. This is really the case for various neurological or neuropsychiatric diseases, such as dementia, schizophrenia, or depression. The applications for brain disease and mental health are real.

As for dementia, a type of problem that alters cognitive functioning and daily living, these applications and derived techniques may be important in various aspects of disease diagnostics, tracking, and even treatments monitoring. Research has already shown that digital technologies could be used to track mood in depression, for example.

Efforts in dementia research are underway. This type of method could provide a non-invasive brain and general health, cognitive, and behavioural evaluation data. This may have real-world implications in digital health trials and rehabilitation. “This approach is especially important for the wide spectrum of diseases characterised by functional limitations”, says an article published in 2015, one of the first to characterise the term.

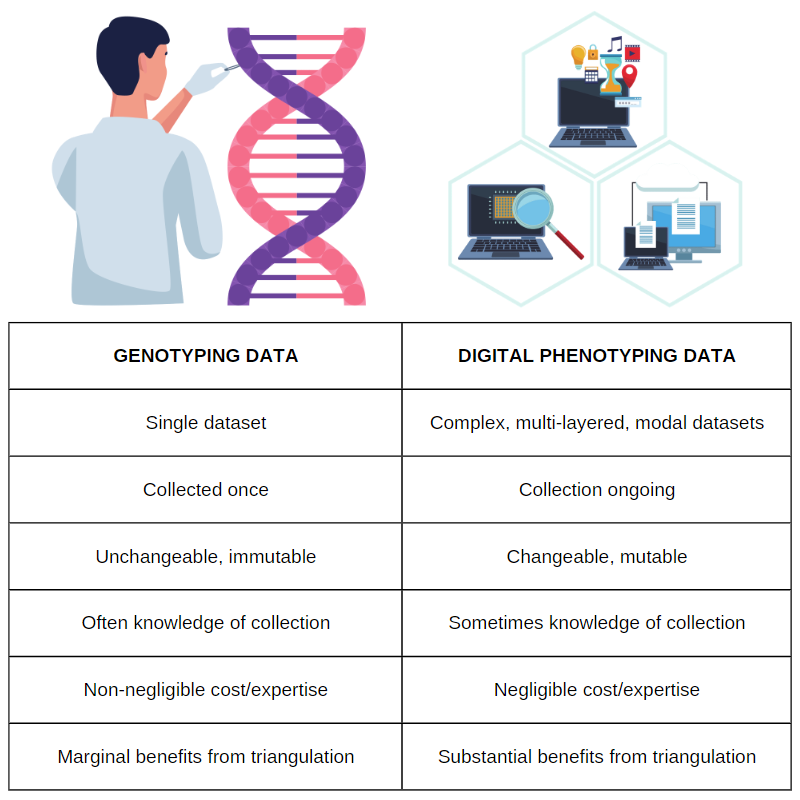

Digital phenotyping has new data generated continuously to reflect changing patterns of behaviour. As an example, we can trace a parallel between this and genetics data. Differences between techniques in patients genotyping and digital phenotyping are shown in the table below. The table is about how these aspects differentiate, tracing a parallel analysis between the genetic vs. digital phenotyping characteristics.

Table 1. Differences between genotyping vs. digital phenotyping data. The author says: “although sophisticated data analysis often requires considerable infrastructure and expertise, the cost of processing and analysing each additional data point is usually negligible”. Adapted from Ignacio Perez-Pozuelo et al (2021). Image credits: mohamed_hassan and kreatikar.

The (ugly) bads

On the other hand, concerns about data protection are not anecdotal. The numbers don’t lie. A recent survey found that 62% of companies in the whole Americas experienced a data breach or cyber incident in 2021. Also in 2021, Brazil experienced a data leakage with more users compromised than its entire population. In the UK, understandable concerns have been directed to patient information systems within the NHS.

All this human interactions with technology could be potentially under (bad) surveillance. And, nothing more precious than our behaviours, cognitive skills, and body ability can be tracked. They can potentially be used not in our favour. Perez-Pozuelo et al (2021) gives an example of third-party companies using healthcare data shared under business associate agreements. They also affirm:

“Several complex issues must first be resolved, such as who owns, controls, and can use personal health data to derive wider insights; the formats and standards that should underpin how these data are shared; and how the range of potential uses of personal data are explained and justified to data subjects.” Digital phenotyping and sensitive health data: implications for data governance, Perez-Pozuelo et al. (2021)

The (untamed) future

Although public entities and the central governments hold a lot of our data, our day-to-day digital interactions are somewhat not in their power, but usually stored and managed by tech companies. Their responsibility is very big.

The question that comes to my mind is that, if this data privacy is really a collective human right, and could bring benefits to all of us, how are the current efforts to secure these de-identified databases for public research beyond the companies walls? Should they be used as a research collective good? How would this be implemented? Is this possible? Lots of questions.

I really believe a way better data handling balance is possible, and rules should be placed clearly. Well built digital technologies could bring immeasurable value for the communities, patients, caregivers, and also for the research teams and private entities. The needs will eventually shape the technology adjustments, considering the fact we have a general positive view for digital technology solutions for our dementia patients. We should participate more in the technology development processes for healthcare.

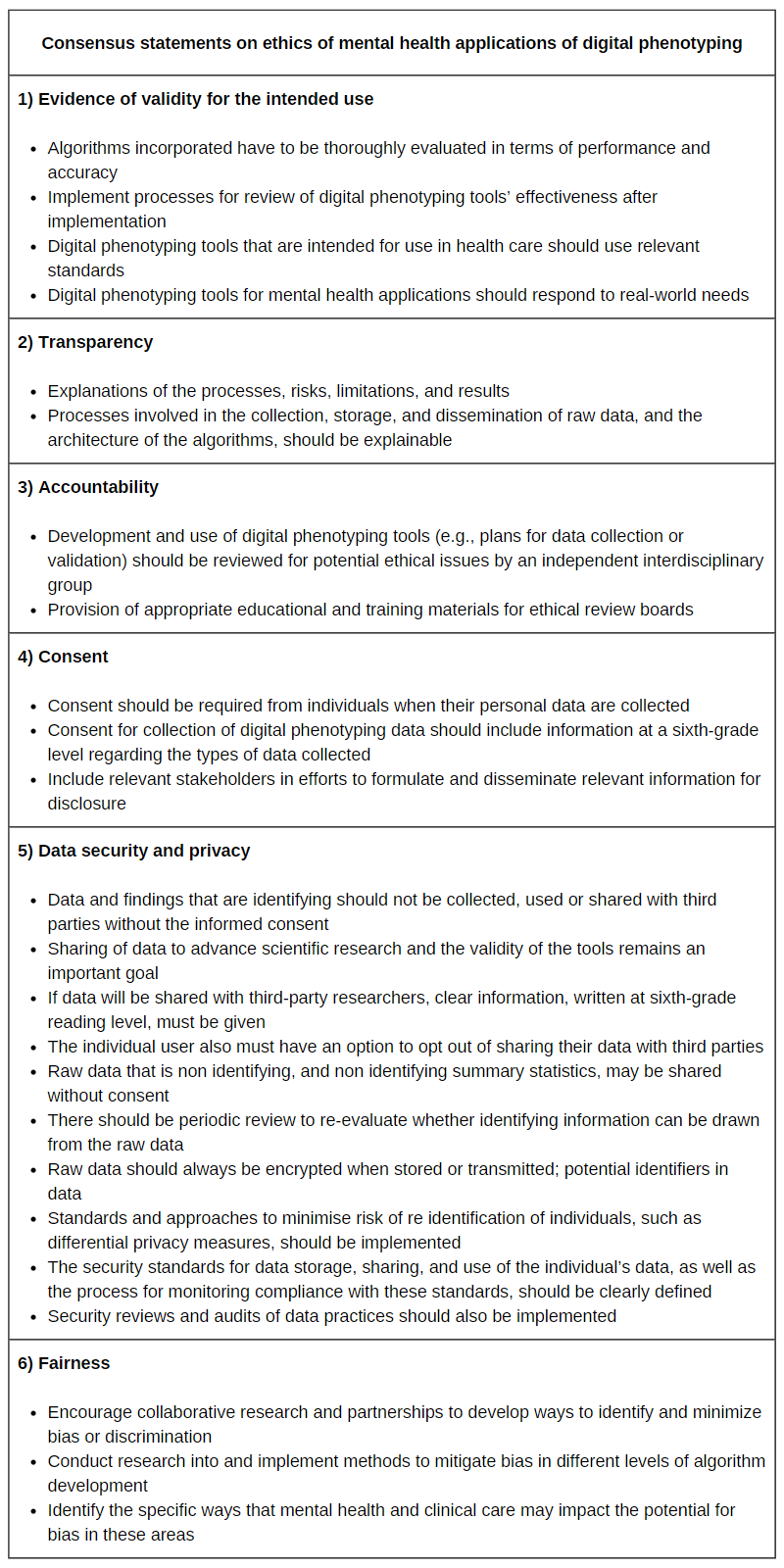

Some nice efforts and calls for action are in place. It is already possible to find statements and consensus about using digital phenotyping for mental health in Pubmed. Table 2 shows some findings of a research group from Center for Biomedical Ethics and Stanford Law School (Stanford University).

Table 2. Data table adapted from Martinez-Martin et al (2021), JMIR mHealth and uHealth.

More than health personnel, interdisciplinary researchers are the one that seem more concerned about these ethical and social implications, and interdisciplinarity may be also an important aid to solve the puzzle. Legislators should be approached and acknowledged about the situation. We, as healthcare providers in mental health, and academics involved in research and education, should educate more, and talk more about that.

Dr Alan Cronemberger Andrade

Author

Dr Alan Cronemberger Andrade is a Neurologist and MSc Student in Neurology and Neuroscience at the Federal University of São Paulo in Brazil. He takes care of patients with neurological problems in diverse settings, and studies how digital technology interacts with the human brain in health and disease, focused on dementia and related disorders. His aim is to find how useful digital technologies could be in the near future, helping dementia patients and their caregivers. He loves writing, travelling, and reading about curious facts of ancient history.

Print This Post

Print This Post

[…] https://www.dementiaresearcher.nihr.ac.uk/guest-blog-digital-phenotyping-in-dementia-and-neurology-w… […]