Questionaries are one of the most common data collection tools in the business along with interviews and focus groups. You’ve probably completed one, or at least been asked to. Yet if you’ve never designed a questionnaire there’s a lot more to it than meets the eye. After recently developing questionnaires for the first time I would like to help others avoid my self-inflicted misfortune by offering some guidance.

Questionnaire content (questions and how to pick them)

Firstly, you need to know what content is needed to address the objectives of the questionnaire. For example, if we were exploring the effects of self-care workshops on unpaid carers personal wellbeing we may look to the dimensions of wellbeing to develop our content and use ‘subjective wellbeing’ scales.

Once you have scoped out the content needed it is useful to draw on secondary data and consider what data has or is already being collected/monitored in the area. Depending on the context, research stakeholders may already be routinely monitoring their activities, data that could be used in your project to avoid duplication and research waste.

Questions and how to develop them

You may use closed, open-ended, and response-option questions, and it’s not uncommon to use a mixture. But bear in mind the target groups and the analysis stage. If the respondent doesn’t understand the question it becomes redundant and may skew the results. Also, how we wish to analyse the data should inform the content and types of questions posed. For example, what variables we want to control for (i.e. household income and isolation), and the analytical techniques used to do so (i.e. regression).

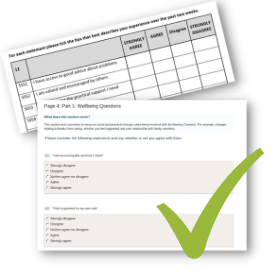

In my case, I used standardised questionaries to test previously developed hypothesises that mainly included closed and response-option questions. An example of a closed question would be, ‘What is your highest level of education completed’, in which the respondent could answer one of the following: ‘Secondary school’, ‘College’, and so on. By adding an ‘Other’ option it becomes a response-option question because the respondent can input their answer manually.

The majority of questions posed in questionnaires are from validated scales that demonstrate adequate reliability and validity with a representative sample. In theory these are considered the most rigorous, though with some of them dating back decades you may find the terminology lacking cultural and contextual relevance to your research. In my opinion, and others who have done similar, it is perfectly fine to adapt scales to better reflect culture, context, and comprehension. If anything this should enhance the overall validity.

But what about if you can’t find suitable scales? Well you can develop your own. This is done by firstly operationalising complex and often vague constructs into measurable variables (i.e. social value). Selecting the most appropriate conceptualisations, definitions, characterisations, descriptions of the construct and identifying the key attributes. For example, based on the description below we can see that social, economic, and environmental security are the dimensions through which the construct ‘social value’ is enabled.

“The Public Services (Social Value) Act came into force on 31 January 2013. It requires people who commission public services to think about how they can also secure wider social, economic, and environmental benefits.”

Taking these attributes questions can be constructed to provide a composite measure of ‘social value’. Three variables for each construct are recommended for face validity. For example you could ask a commissioning officer; ‘We have considered social benefits in our commissioning of public services’, in which they can answer, ‘Strongly agree’, ‘Agree’, ‘Neither agree nor disagree’, and so on. Repeating the question for economic and environmental dimensions. You can then tally up scores for a measure of ‘social value’ that has been operationalised in your research.

There is a great ‘how to’ video on developing scales that is way more extensive and sophisticated than I provide here, so take a look.

Don’t get lost in the questions logic…

Constructing your questionnaire

Now you have the ingredients, you need somewhere with the tools to build your questionnaire. The institution you are affiliated with will likely have a platform for such like JISC or Survey Monkey. Even if your unaffiliated to an institution most platforms allow you to build questionnaires for free, although there are limits, for example on number of questions and responses.

In some cases the best place will not be a specialist platform. I have found Microsoft Word to be a good tool that allows you to have greater control of the design such as layout of questions, line spacing and other design details that can make the questionnaire more accessible, and importantly, shorter. However, be aware, purpose-built platforms offer excellent analytical functions that produce information such as mean, median, and standard deviation instantly, and also allow questionnaires to be accessed online.

Other things to consider is the structure and flow of your questionnaire. Grouping questions into sections that are similar in content or structure, introducing sections and defining key terms will only enhance the quality.

Pilot the questionnaire

Unless you’re the sample, you won’t know how good your questionnaire is until you pilot it. Asking people representative of the target population to complete the questionnaire and consider accessibility (terminology, scales, structure, and format), and relevance of the questions (there may be more/less needed) is perhaps the most important step of all.

Distributing questionnaires

Ignoring that distribution is being discussed lastly here, it should really be considered at the outset as it will influence the design of the questionnaire. You can use Email, postal, QR codes, App, Website, physically in person, and phone calls to get your questionnaire out there. Although you should always consider the population you’re trying to reach and the ethics and bias inherent in your sampling procedures. For example, online distribution may exclude people without internet access.

There is also some advice on steps to consider that precede designing questionnaires that I haven’t covered in this post. So please do check them out.

Nathan

Further reading: Sudman, S. and Bradburn, N. M. (1973), Asking Questions, pp. 208-228

If you found this blog useful, then check out this podcast from our recent ‘Methods Matter’ series

Nathan Stephens

Author

Nathan Stephens is a PhD Student and unpaid carer, working on his PhD at University of Worcester, studying the Worcestershire Meeting Centres Community Support Programme. Inspired by caring for both grandparents and personal experience of dementia, Nathan has gone from a BSc in Sports & Physical Education, an MSc in Public Health, and now working on his PhD.

Print This Post

Print This Post