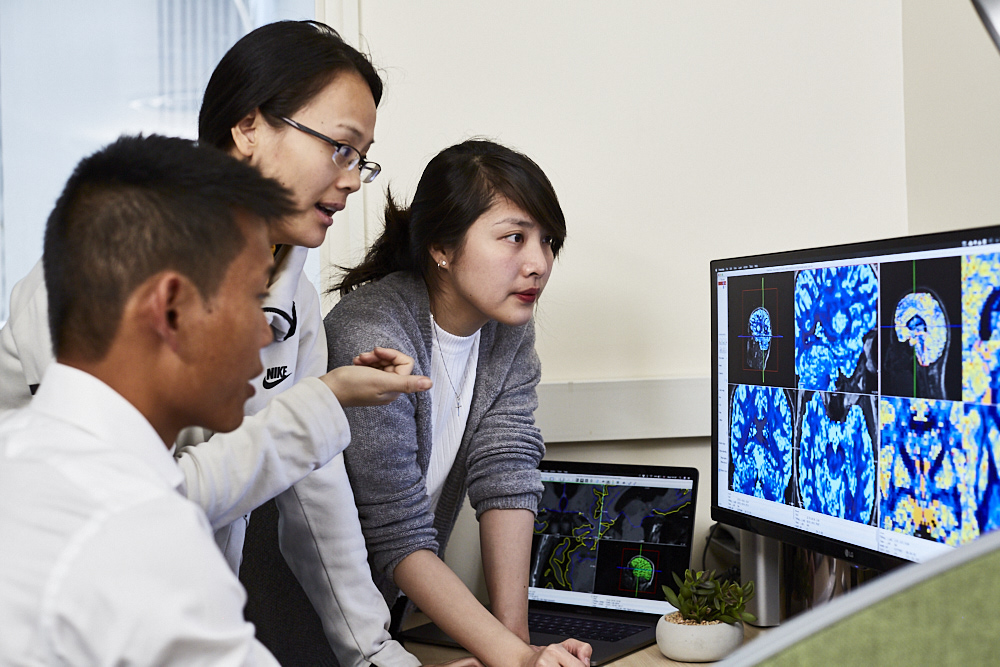

Collaborations and partnerships are key to research across all fields and are often formed naturally within academic circles. Here we explore how partnerships outside of academia can help to translate research findings into practice.

The Alzheimer’s Society Research Translation programme

At Alzheimer’s Society, we encourage all of our researchers, particularly care researchers, to consider how partnerships might be relevant to their work. Engaging with those outside of academia could improve the relevance and impact of their research.

Find out more about working with our Research Translation team.

Alzheimer’s Society has championed the role of people affected by dementia in research, which is now increasingly common practice. However the involvement of other stakeholders, including practitioners, commissioners and policy makers is less well-established.

Partnering successes

At the 2019 Alzheimer’s Society’s annual conference, we hosted a session for researchers on working in partnership with those outside of academia. Four researchers shared their experiences of carrying out research in partnership which are summarised below:

- Reena Devi from Leeds University talked about her involvement with NICHE, a partnership with two local care homes. Researchers are embedded within the care homes, where they work with staff and residents to identify research questions. They are then able to translate existing findings into daily practise or seek funding to tackle unanswered research questions.

- Kevin Muirhead from the University of the Highlands and Islands talked about his research in partnership with CogniHealth, a healthcare company developing digital technology to support carers. Working together has enhanced Kevin’s PhD and enabled Congihealth to ensure the technology they’re developing is evidence based.

- Robyn Dowlen from the University of Manchester talked about carrying out her PhD in partnership with Manchester Camerata, a music company. Her supervision was split between the University and Camerata. This ensured her research was directly relevant and useful to the company but was also delivered to a high academic standard.

- Francesco Tamagini from the University of Reading talked about the benefits of involving people affected by dementia in his biomedical research and the public understanding of work being done. The continuous interaction with people living with the condition enabled him to acquire a better perspective on how he could make his research more relevant and impactful.

Challenges

There are many benefits of working in partnership to improve the impact of research; however we recognise that it’s not always easy in practice. There are a number of challenges that may arise such as:

- Timescales for research

The academic process takes time. The pace and environment is very different to companies which can work at a faster pace and often want answers ‘yesterday’. It’s important to be clear and set these expectations from the start.

- The balance of power

Working in partnership requires a balance of power and shared decision making. However researchers go through a high level of training to become experts in their field and so adjusting to leading a project collaboratively can be difficult. Effort needs to be made to establish relationships and ground rules from the beginning in order to work together effectively.

- Funding that allows for flexibility

To work collaboratively in a meaningful way, the research process needs to be fluid allowing for solutions to emerge as the project develops. This can be hard with the nature and governance of research funding. There is a growing need for funders to be flexible and recognise the value of research carried out in partnership, which needs to be assessed differently to more traditional research.

- Producing publishable findings

There is pressure from academic institutions to produce publishable findings. This can sometimes feel contradictory to carrying out research with practical applications. Tensions can form between the push for more theoretical new knowledge, compared to research to solve a practical problem. Ultimately this can force researchers to make decisions about their career paths.

- Agreeing shared goals and outputs

It’s useful to agree what the expected outcomes need to be from the start. Difficulties can arise when findings are not favourable to partner organisations, and they may decide not to use the evidence based recommendations. It’s important that partners feel a shared ownership of the findings which can be achieved through continuous engagement between partners throughout the process.

Alzheimer’s Society’s Care Collaboration grants

Alzheimer’s Society recently announced a new ‘Care Collaboration’ grant scheme, to develop and test models of partnerships between researchers and care providers.

The funding is flexible and focused entirely on the collaboration. We expect the dynamic of the research to change, so researchers and care providers are both seen as the experts and make decisions together to achieve a joint understanding and ownership of the research. Through this collaborative approach, we expect research findings to be relevant and useful to the intended audience, leading to the successful implementation of findings into practice.

Supporting partnerships

Alzheimer’s Society will continue to be flexible in our approach to funding to ensure we fund research that generates relevant solutions, whilst also retaining the scientific rigour.

We encourage all applicants to our funding schemes to consider working with partners outside of academia to increase the relevance and usefulness of their research findings. This could include, but is not limited to, practitioners, policy makers, commissioners, industry partners as well as people affected by dementia.

If you require any information or support on this topic, please contact a member of our Research Translation team at research.translation@alzheimers.org.uk.

Author

Nicola Hart works as a Research Translation Manager for the Alzheimer’s Society in the UK. Nicola’s work helps ensure dementia research findings are brought to the people who need it, when they need it. Which is important when you consider that today, only seven per cent of research is taken into practice – and that can take up to 17 years. Find out more about Nicola’s work and engage with the team here.

Print This Post

Print This Post