I am Amelia, and this is my first blog for Dementia Researcher. I have worked in clinical research focussing on Dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer’s disease for over 2 years. I will share with you the ups, downs, and most definitely sideways you will encounter as a research assistant. The main part of my job involves setting up polysomnography (PSG) sleep equipment on patients. PSG can diagnose sleep disorders by measuring brain waves, blood oxygen levels, and heart rate. It can easily determine sleep stages and cycles. I attach 20 electrodes to the face and scalp, then a body kit to the chest connecting everything together.

You’re probably accustomed to working with patients older than you, if you’re a young dementia researcher like me – yes, 24 is still young. I live to believe we are all 2 years younger than our birth certificate age thanks to COVID-19 making us lose valuable years of our lives. Whilst young onset dementia is prevalent in UK patients (7.5% of dementia sufferers) my research project requires patients to be 60+. So how does one with green stripes in her hair, tattoos, and piercings, converse or connect with someone triple their age? Well, that’s an age-old question…

As cliché as it seems, I have found greeting patients with a smile helps them to know I’m not about to storm into their home, steal their beloved items, and criticize Eastenders playing in the background. Coaxing yourself into a positive mood can be difficult after a hard day or a long, solo car journey to a patient’s home. However, that initial interaction is worth the effort of putting on a Cheshire cat grin. Smiling helps you appear welcoming, warm, and non-threatening- which can lead to more positive experiences.

It’s crucial for me to develop a good initial rapport with my patients and caregivers. I am the only researcher on the project and meet with the same participant multiple times, including evening visits. I want my patients and their respective household members to know they are in safe hands, and I am someone they can trust. Wouldn’t you if a stranger (albeit a professional one) was coming into your home for 6 mornings and evenings to attach equipment to you?

I’d like to take you back to 2022, it’s my first time visiting a patient. I’m inside their house and ready to begin setting up the polysomnography equipment. The initial awkward hello, how’s your day, here’s the rundown for this evening has been done and it’s time to get down to business.

Working with different generations can be difficult – but always remain pleasant, curious, and open. You will be surprised at what you can bond over.

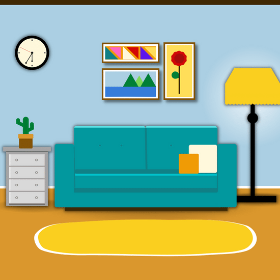

I could set this equipment up blindfolded. I have practiced over and over on a glass model head. I know the protocol like the back of my hand. This will be smooth sailing! But… WAIT! What on earth do we all talk about now? The caregiver is usually sitting on the sofa and the patient on a dining chair, both facing the television. The silence of the living room dawns on me, the TV adverts have started so there’s nothing else to concentrate on, and you could most definitely hear an electrode drop. There is an unspoken pressure here – I am the professional, I am running this research and therefore I need to take control of this conversation. But… WAIT! This is their home… it’s late at night… what if they don’t want to talk? What if they have already predicted how little in common we have and decided it would be best to continue this deafening silence? But WAIT… NO! You must break this. ‘I really like the owl ornament on your fireplace’ …

That right there is the best conversation starter in someone’s home. Compliment their décor and you have gained access to their voice box. It never fails to get the conversation rolling. ‘Where did you get it from?’… ‘TK Maxx? I love shopping there too!’ I locate something in the room I like or have knowledge on, so I can show genuine interest and curiosity. You will find that once you get your patient or caregiver talking, it’s extremely easy to continue the flow of dialogue. Ask them follow up questions! Most of the time these people are happy to have someone to talk to and share their life history with. Almost every time I leave a patient, they say they will miss my usual visits and company. That’s just one part of working with dementia that tugs on your heartstrings.

It does of course help if you are a 24 year old with similar hobbies to a 64 year old. Although I’m biased, I would recommend anyone picking up these hobbies. They not only make great conversation openers but are good activities for your mental and physical health.

Birdwatching – Pretty much every elderly person I encounter likes to bird watch in some capacity. This opens a world of questions: What birds do you get in your garden? Do you feed them?

Stargazing – Again, stargazing seems to be a very common topic in this cohort. Maybe as you get older you look up at the sky more. If they are avid stargazers, I like to tell them about my Cassiopeia constellation tattoo (I’ve managed to beat all stereotypes AND feed into their hobbies… score!) One couple I met lived in Iceland for years and explained they would often walk home from bars in the early hours and would see the Northern Lights in full display. How cool!

Gardening and nature – Where will you find your grandparents on a weekend when the sun comes out? The garden. Funnily enough, that is where you will also find me (no one told me how much upkeep cutting your grass is.) It’s difficult to find someone over 60 who won’t be up for talking gardening tips, good nature walking routes, or what garden centres are best.

Animals and pets – I’m an animal lover and could talk about them until I’m blue in the face. So, when patients watch Dogs Behaving Badly or they have a labrador running around the living room, it’s very easy to find things to talk about. How long have you had your dog? Do you often watch animal programmes? You have the pleasure of meeting animals you’d unlikely come across. For example, one of my patients had 2 Oriental Shorthair (Siamese) cats. Very rare and extremely beautiful!

We’re not just researchers, but conversation starters, holders (and sometimes enders but that’s for a different blog post)! It’s part of the job that is unmentioned, yet necessary. Once mastered, it makes the process of meeting new people in a home setting easier and can increase participant retention rates. If you’re a young researcher going to their first home visit, and slightly introverted like me, don’t put tons of pressure on yourself. The likelihood is they’re just as nervous. Confidence is crucial and even if you must fake your confidence… who will know it’s not real?

Working with different generations can be difficult – but always remain pleasant, curious, and open. You will be surprised at what you can bond over.

Thank you to the patients and caregivers who welcomed me with open arms to their homes and allowed me to conduct research during delicate and precious times.

Amelia Robson

Author

Amelia Robson is a Research Assistant at Northumbria University supporting delivery of NHS Clinical Trials, particularly in working with Dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer’s disease patients. This work currently involves visiting patient’s homes and applying polysomnography sleep equipment on their face, scalp and body. Amelia graduated in Psychology in 2021 and is passionate about supporting people living with the dementia, and providing help for care givers. Her top tip…. Trust your Gut to stay on the right path.

Follow Amelia Robson on LinkedIn

Print This Post

Print This Post