For many new PhD students, the idea of managing a research project can feel overwhelming. You’re tackling complex questions, gathering and analysing data, managing time and resources – and all while trying to keep your sanity intact. In many ways, research is just like any other project, and using some tried-and-tested project management principles can make the journey a lot smoother.

My own background is in Project and Programme Management, and in a recent Dementia Researcher Salon webinar discussing Study Recruitment, we got on to talking about risk registers, and mitigations and templates… and I was surprised when few of the guests and audiences has come across this approach. This got me thinking… we often tell PhD students that their work on managing studies can be translated as ‘project management’ when it comes to looking for jobs outside of academia, but are there elements from project management that could be perhaps aren’t used in research delivery?

So, what exactly is “project management” in this context? Essentially, it’s about having a structured approach to planning, organising, and handling tasks so you can deliver what’s needed – on time, on budget, and to a high standard. PRINCE2 is one well-known project management framework that can be useful, especially for projects that need clear structure, but it’s far from the only way to organise things. You don’t have to adopt any one framework wholesale to get benefits from project management thinking; often, it’s just about picking up a few tools and habits to make things easier as you go.

Let’s start with planning. Project management usually kicks off with setting out the project’s scope – which is just a fancy way of saying, “What exactly am I trying to do here?” Most researchers already do a version of this, especially when writing a proposal or setting research objectives. The next step in project management, though, is breaking those big goals down into smaller tasks or “milestones.” For instance, instead of thinking about your research as one big task, you might break it down into parts: literature review, data collection, analysis, and writing up (there may be overlaps, but you get the idea). This approach can help make things feel more manageable and gives you a clear roadmap to follow.

And speaking of roadmaps, timelines can be lifesavers in research. A simple Gantt chart, which shows tasks along a timeline, can give you a bird’s-eye view of what needs doing and when. It’s one of those classic project management tools, easy to make (even in Excel), and helpful for spotting any time clashes. When used regularly, it lets you forecast your time – which is essentially just a way of planning how long you think each phase will take and adjusting as you go.

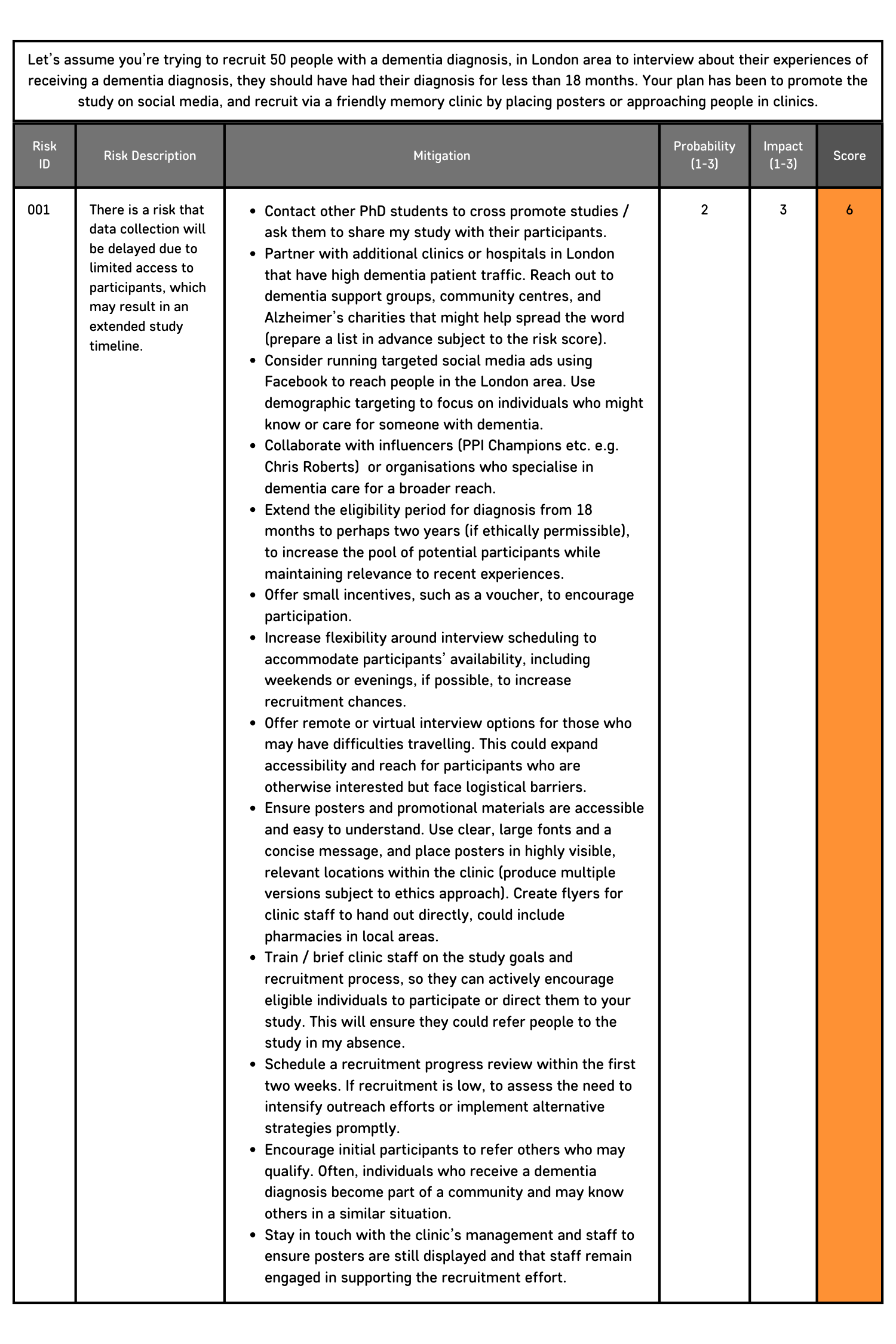

Then there’s risk management. This is an area where frameworks like PRINCE2 shine, as they encourage using a “risk register.” Now, that sounds very official, but it’s really just a list of potential issues that could throw your project off track, along with ideas for how you’d handle them. Say you’re worried about recruiting enough participants – you could include that on the list and jot down any backup options. This doesn’t need to be anything fancy, but by having it written down, you’re ready to address problems before they get too big. Even a basic list of “what ifs” and a few practical responses can give you more control – if done in advance this forces you to think through what you would do if something goes wrong, so you’re ready to act. Below is a little example I have quickly thrown together of what a risk register entry on study recruitment might look like (you would then do the same for everything else, e.g. delays due to illness, or something not arriving in time, equipment failure, lack of data…).

Example of what an entry into your risk register might look like. There would generally also be an ‘update’ column for you to talk to progress, any issues, if the risk has been realised. Keeping a full risk register table, up-to-date and on a share drive, could be a way to give your supervisor and stakeholders a way to keep updated on any issues, without you needing to constantly contact them, as part of your assurance framework.

The probability and impact columns are something you will have to judge, and you can ask others for their input to this, then you simple times one number by the other to give you a risk score, everything with a high score is red, middle is amber and low is green. Then in your plan you would review risks based on their score e.g. Red risks might be reviewed every two weeks, amber every month, and green every two to three months. You can also keep your mitigations up to date.

Quality control is another big project management concept, and it’s especially useful in research. When project managers talk about “deliverables,” they mean specific outcomes or tasks that need to be completed at each stage. For research, you might think of these as your key outputs – like a draft chapter, a pilot study, or a final analysis report. By aiming for clear deliverables in each phase, you ensure that your work is meeting the necessary standards, bit by bit. Plus, it can make feedback from supervisors a lot easier to manage when you’re only focusing on a specific part, rather than the entire project at once.

Then there’s documentation. Project management frameworks like PRINCE2 come with ready-made templates for things like risk logs, issue lists, and project plans, which can keep your work organised. You don’t need to adopt these exactly, but borrowing the idea of having consistent records can help. Simple documents that track your plans, timelines, and decisions can be a big help later on, whether you’re writing up or explaining your project’s direction to a supervisor or funder. For many researchers, just having a list of milestones, a project timeline, and a risk register is enough.

Project management can also help you judge when it’s time to reach out to your supervisor for support or advice. Many project management frameworks, PRINCE2 included, talk about “project tolerances.” These are basically limits on time, cost, or quality that, if exceeded, mean it’s time to escalate the issue to someone else. In a research setting, think of tolerances as boundaries you’ve set around your timeline, resources, or outcomes. For instance, if your data collection is taking twice as long as expected, or if a critical piece of equipment is unavailable, these are signs you might need to flag up the issue with your supervisor.

By having these limits in mind, you’ll know when things are drifting off course and can seek help sooner rather than later. This approach prevents last-minute scrambles to catch up and gives your supervisor the opportunity to support you more effectively. Then, when you meet with your supervisor you can have all this information at hand, and add as a standard item to your agenda.

On the subject of keeping supervisors informed, this is where project management tools can also help, and doesn’t have to be complicated, either. Project management principles often suggest simple, regular updates to make sure everyone’s on the same page. For research, this could be as easy as preparing a brief summary of progress, issues, and next steps before each supervisory meeting. This might sound like extra work, but it actually saves time in the long run by helping everyone stay aligned. You could even use a simple status report template to track these updates. This doesn’t need to be long – just a quick note of where you are, any issues you’re facing, and any decisions you need help with.

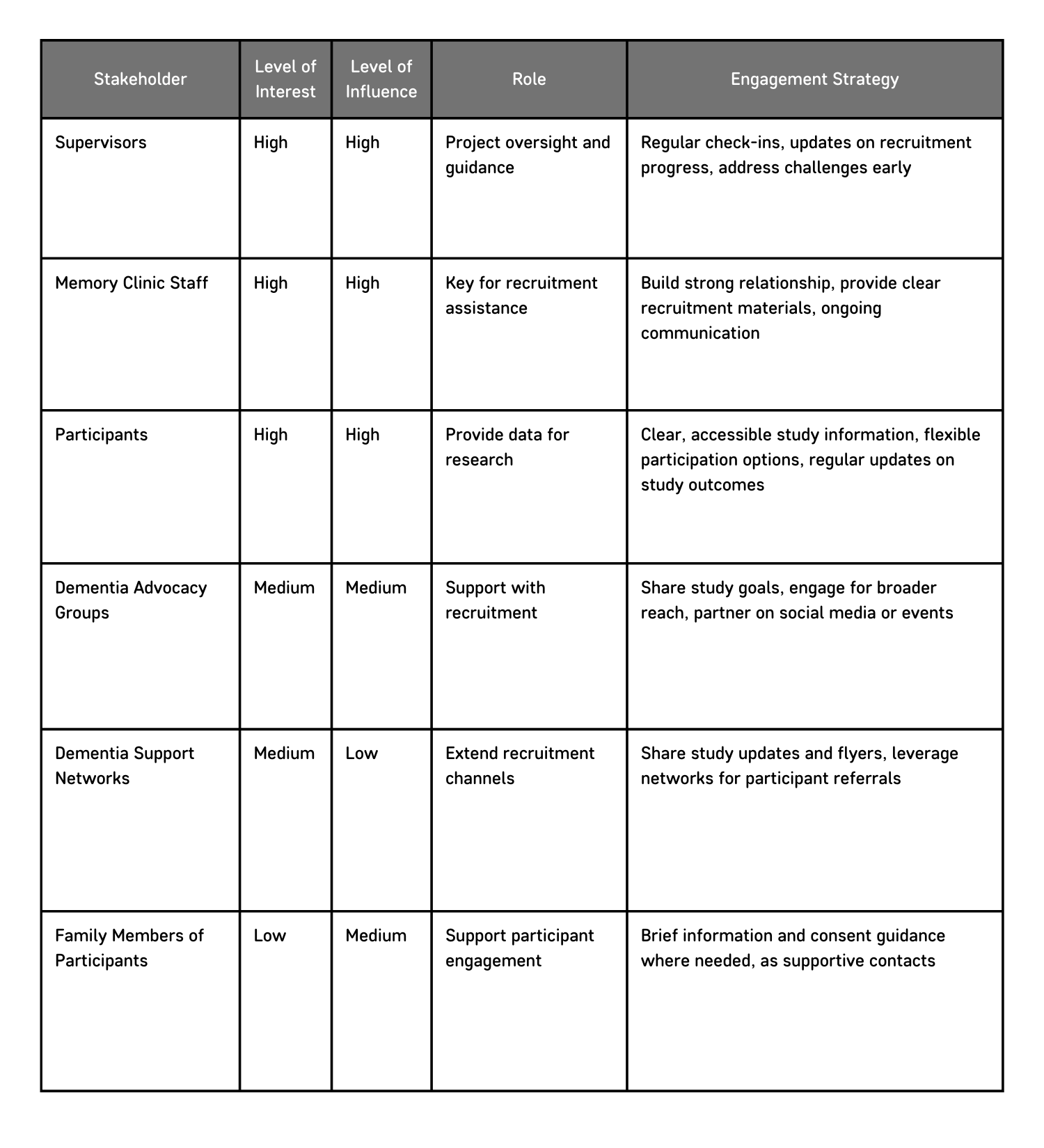

Finally, let’s talk about communication – in project management, it’s often called “stakeholder management.” In research, this means keeping supervisors, collaborators, and study participants in the loop. Project managers often set up regular updates to make sure everyone’s on the same page, and it’s a habit that can work well in research, too. For example, setting up regular progress meetings with your supervisor can prevent miscommunication and help spot any issues early. You could also do some stakeholder mapping to help you plan, below is another example.

This example is probably more suitable for those working in qualitative research. However, the same principles apply for those working in fundamental science. This could be Lab Technicians, Collaborators or people involved in your study.

The above can also inform your communications plan, I gave a talk on this, which you can find on YouTube.

There is much more I could get in to, but I’m already over 2,000 words which is long for even me! However, if you’re interested in reading further, there are some great resources that explore project management in an academic setting. The book “Planning Your PhD: All the Tools and Advice You Need to Finish Your PhD in Three Years” by Hugh Kearns and Maria Gardiner is a good starting point, as it discusses various aspects of project management tailored to research. They also provide a bunch of free templates for thesis planning. For something more hands-on, you might look at PRINCE2’s official resources for templates or check out “The Project Management Book” by Richard Newton, which is a practical guide on general project management skills without too much jargon, and also the PRINCE2 Wiki with templates.

At the end of the day, whether you use PRINCE2 or just pick a few useful tools, adopting a project management mindset can make the PhD experience a lot more manageable. It’s all about creating a bit of structure, so you can handle whatever your research throws at you with a little less stress.

Adam Smith

Author

Adam Smith was born in the north, a long time ago. He wanted to write books, but ended up working in the NHS, and at the Department of Health. He is now Programme Director at University College London (which probably sounds more important than it is – his words). He has led a number of initiatives to improve dementia research (including this website, Join Dementia Research & ENRICH), as well as pursuing his own research interests. In his spare time, he grows vegetables, builds Lego, likes rockets & spends most of his time drinking too much coffee and squeezing technology into his house.

Print This Post

Print This Post